The Failures

What they can teach us... eventually.

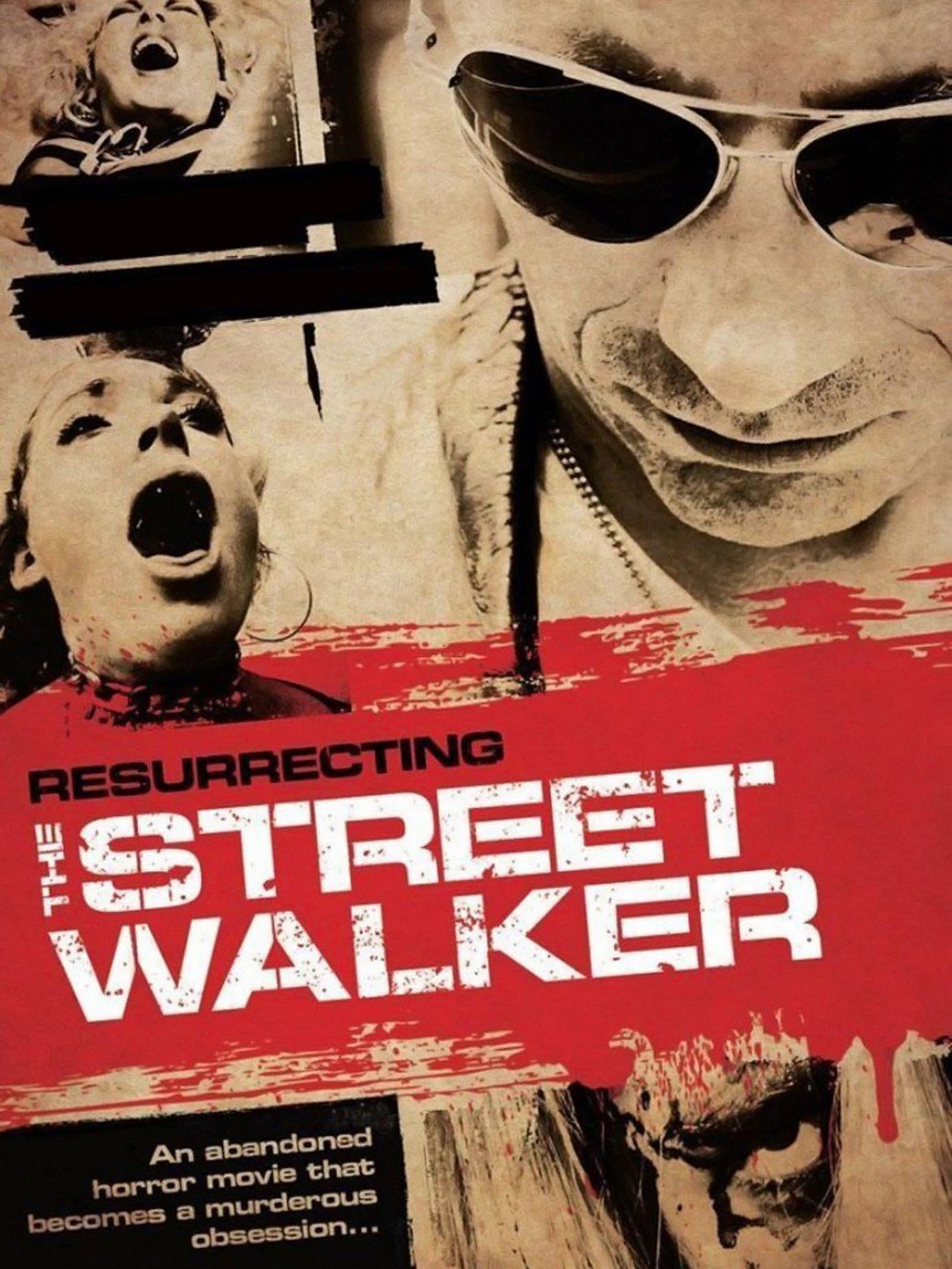

In 2006 (oh, boy, that was 19 years ago!) I conceived of a project that I was—using the risible industry parlance—passionate about. The working title was Celluloid Dreams, a rather desultory name that has been done to death, and by 2010 it had become Resurrecting the Streetwalker, a more original title for the feature-length horror film that went on to attain cult status (if “cult status” means that only a handful of the most ardent horror film aficionados have ever heard of it).

Arguably, I was more passionate about the marketing of the film than the film itself during the making of it, I’ll freely admit. My sense was that the internet was going to be big (whaddaya know, I was right, along with about a billion other “sages”) and I wanted the film’s characters—or personas—to exist online. So, of course, the first thing I did was create a MySpace page for the protagonist, James R. Parker.1 Remember MySpace? It was the first Facebook type thing that got any traction. I wanted audiences to believe that he was real, you see, and, I suppose, I was planning some sort of a hoax like The Blair Witch Project but—as the cliche goes—on steroids (multi-media was all the rage back then, kids).

Additionally, I made videos of James interviewing film producers like Julie Baines and the late Nik Powell from the British film industry he (fictionally) worked in, at a ramshackle but vibrant office in Soho, and uploaded them to his YouTube channel (this was a new thing at the time). Then Facebook happened and I migrated James to that platform and shared posts once in a while in parallel to the storyline of the film in order to get a “buzz” going. At around the same time (as social media and streaming really took off) the bottom fell out of the DVD market where we had planned to make our money back. Oops. Thankfully, the film didn’t cost that much to make and all the investor’s wrote off their money and went on with their lives, including me.

Needless to say, the multi-media approach didn’t work for us. I didn’t know what I was doing exactly and there was no heft behind the execution. All my efforts in the freshly blossoming arena of social media fell flat and they did nothing to support the (quiet) launch of the film by the distributor who didn’t really care about what I was trying to do online, unlike Artisan Entertainment who released Blair Witch in 1999. I mean, they had a point: hardly anyone picked up on the James R. Parker internet stuff and thus it added nothing to the concept of presenting a fake documentary in the horror genre as a real documentary. I was trying to outdo the American film from a decade earlier that spawned a thousand imitators and I failed. To be fair, some audience members at film festivals and critics alike actually commended how real it seemed to them (a gratifying feeling) and we had one woman walk out of a screening in Aberystwyth because she thought it was a documentary and she was disgusted by James and his nasty shenanigans. God… I hope someone ran after her and told her it was all fiction!

I exaggerate a lot and I get fiction and reality mixed up, but I don't actually ever lie.

Lucia Berlin

You might say, hey, just make a great movie and don’t worry about the marketing, but, you see, I saw the “marketing” as part of the movie—after all, the movie was about movie making itself and Parker’s quest to finish an abandoned 1980s horror flick, which had become the subject of a (fake) documentary. That was the whole conceit and, consequently, it made perfect sense to bolster the metafictional aspects of the project by embracing other media in the conception of the whole. Made sense to me anyway: I wanted to express the (admittedly vague) idea of a coming onslaught that I now term The Big Blur. The blending of fiction and reality in filmic form and RTSW was what came out. Now I’m working on a film called This is Not a True Story, which is based on real events and it’s about a man who adapts his screenplay into a novel because he can’t get it made for political reasons in his home country and then goes into exile to turn his Kafkaesque experiences into a London stage play. And I’m passionate about it, okay?

The source of my monomaniacal focus on metafiction is a mystery to me but I do know that I enjoy films about making films and films-within-films like Lynch’s Mulholland Drive or Inland Empire and plays-within-plays (Shakespeare was a fan of the device too) and even plays-within-films, for that matter. In literature, I love Mikhael Bulgakov’s Black Snow about a suicidal novelist who has his failed novel adapted into a play—with hilarious results. There’s something deliciously voyeuristic about seeing those worlds that themselves run on voyeurism get brutally satirised as—a bit like the campus novels of Nabokov—they entertainingly reveal the inflated egos and insane levels of dedication that teeters on the knife edge of self-delusion exhibited by those who work in such hallowed arenas. Yes, having undertaken a PhD, I do think that academia, the theatre, and filmmaking are somehow extremely similar milieu. Not to mention the world of contemporary art, which I satirised in the novel Conception (Fairlight Books, 2020).

Since making films takes so much money that I don’t have and have failed to raise in full,2 I am turning to the novel once again to write more about the people who inhabit the world of filmmaking. You can take the man out of filmmaking but you can’t take the… etc. It’s called Love, Create, Destroy and it’s my fondly scabrous love letter to cinema. Maybe a break-up letter, actually 😩.

Meanwhile, unable to commit to turning my back on film completely, I made a short film with what I had (me, a camera and some old footage). And here’s the trailer for it:

On a brighter note to end this post about failure, metafiction is doing well; now more than ever, and is booming all over the place. In no small part thanks to the meta-reality of the narratives unspooling via the Word Wide Web—and I am still trying to work out why it’s so fascinating. Perhaps it’s fascinating because the blending of truth and fiction is our imaginative way of echoing what is happening to us as a species. It holds the clues to humanity’s future maybe—a stepping stone to dispensing with our corporeal selves altogether as our consciousnesses migrate to non-biological substrates, a theme taken up by the emergent field of technoetics that researches the impact of the digital realm on consciousness. By the way, I just watched a Polish film uploaded to YouTube called Photon and it profoundly resonated with this notion. A huge shift is already underway. But I digress…

I came into filmmaking from painting. In painting… you do everything—you don’t have somebody paint the blue and another person paint the red—you do everything…

David Lynch

Ultimately, what did the failures of RTSW teach me, then? Filmmaking is a team effort and you can’t do everything yourself just because your ego wants you to (although I must say that Norman Leto almost gets there with Photon). If you want to be a one-man band then filmmaking is going to be a frustrating experience. Nevertheless, it’s not impossible anymore to do a lot of the work yourself: nowadays, you can do almost everything by becoming a solo online influencer, relying on (dubiously free) technological platforms to support your endeavours, and shoot the thing, edit the thing and publish the thing to the world with no collaborators and no intermediaries!3 And then there’s generative AI that, once the ethics and legalities are addressed, will allow people who have a vision they want to share with the world to dispense with having to use expensive equipment and crews of people at all (it’ll be a sad day for crews, of course). Just you and some compute. Like a painter and their canvas or a sculptor with a block of stone and a chisel.4

But, so far, all we’re getting falls far below what cinema can still do. I’m still waiting for the first truly great online movie made (mostly) by one person working on their own and making zero compromises. Maybe I’ll be waiting forever… but somewhere out there someone is happily failing and learning and getting better, so I still have hope.

The sad and skeletal remnants of James’s page lingers on MySpace.

I’m making little short ones occasionally, but the full-length feature films are stuck in, what we call in this game, “development hell”.

Since you’re reading this footnote you made it almost to the end of this post—consider liking and/or leaving a comment!

I don’t mean working in a solipsistic vacuum: painters and novelists get feedback on their work as they shape them, for example, but what they don’t have to deal with is someone slapping the brush out of their hand as they paint or deal with a pen that tells you to use less words and write faster because it’s running out of ink.

Very deep problems… 👍😔👏

🔥👌🏽 love the Nik Powell Interview, RIP